The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is quickly becoming the standard way for Large Language Models to interact with external tools. At its core, MCP defines how a model can discover tools, understand their inputs, and invoke them in a structured way.

Most MCP examples online are intentionally simple: one model, a few local tools, everything wired together manually. That simplicity is useful for learning, but it hides the real challenges that appear the moment you try to scale MCP beyond a demo.

This article walks through the design and implementation of a complete, real-world MCP system, not just an isolated MCP demos integrated with WEB Interface. The goal is to show how an MCP tool is built, published as a versioned artifact, discovered dynamically, and executed securely—end to end.

This is about turning MCP from a protocol into a working system—one that can run continuously, evolve safely, and support real user queries without hardcoded wiring or manual intervention.

Why MCP Needs an Architecture (Not Just a Protocol)

MCP by itself is a protocol, not a platform. It tells you how a model can call tools, but not how those tools should be discovered, secured, versioned, or executed.

In early MCP setups, tools are usually:

Hardcoded into the LLM runtime

Executed as native processes or via clients like GitHub copilot

Coupled tightly to the orchestrator

This works until you ask basic questions like:

How do I add a new tool without redeploying everything?

How can I expose the knowledge from tools to web clients?

How does the model know which of dozens of tools is relevant for a given use case?

The MCP Workbench exists to answer those questions systematically.

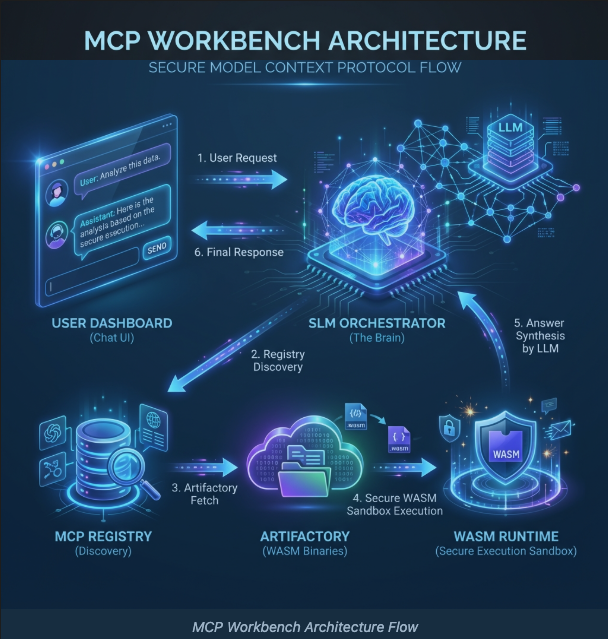

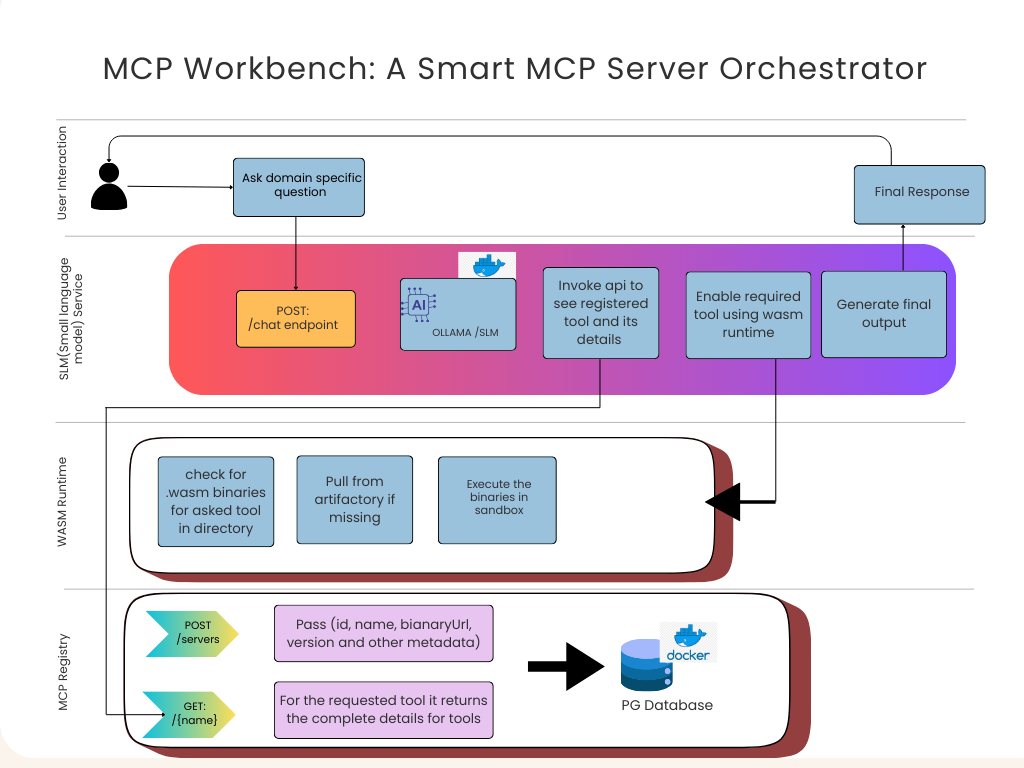

High-Level Architecture: From Question to Executed Tool

At a high level, the system follows a clean request-driven flow, as shown in the architecture diagram above.

A user starts by asking a domain-specific question—for example, “What should I do in Gurgaon this evening?” At this point, nothing about tools is assumed. The question is simply forwarded to the orchestration layer.

The request enters the SLM-based MCP Orchestrator through a /chat endpoint. This is a deliberate design choice. Instead of relying on a large chat model to hallucinate tool calls, the orchestrator uses a Small Language Model (SLM) whose job is narrow and controlled: interpret intent and decide whether a tool is required.

If the SLM decides that a tool is needed, it does not guess where that tool lives. Instead, it queries the MCP Registry, which acts as a centralized phonebook for all available tools. The registry responds with concrete metadata: tool name, version, input schema, and—most importantly—the URL of the executable WASM binary.

Execution is then delegated to the WASM Runtime, which checks whether the binary already exists locally. If not, it pulls the tool from the Artifactory, instantiates it inside a Wasmtime sandbox, and executes it with strict permissions. The result flows back to the orchestrator, which may either call another tool or generate the final response for the user.

At no point does the user—or the model—directly touch execution details. That separation is intentional.

The Role of the SLM: Deterministic MCP Orchestration

The SLM service is the brain of the system, but it is not a chatbot in the usual sense. Its responsibility is orchestration, not conversation.

Instead of relying on a large chat model to hallucinate tool calls, the orchestrator uses a Small Language Model (SLM) whose job is narrow: interpret intent and decide whether a tool is required.

Here is how the orchestration loop handles multi-turn tool calling:

# From slm_server.py

@app.post("/chat")

async def chat(request: ChatRequest):

messages = [system_msg] + request.messages

# Loop to handle multiple tool call rounds (e.g. fetch weather -> fetch activity)

max_turns = 5

for turn in range(max_turns):

# Fetch available tool schemas from Registry metadata

current_tools = get_tools_from_registry()

# SLM decides if a tool call is needed

response_msg = await llm.chat(messages, current_tools)

if not response_msg.get('tool_calls'):

return response_msg # Return text response if no tools called

for tool_call in response_msg['tool_calls']:

# Dynamically execute the tool via the WASM Runtime

result = await session.call_tool(name, arguments=args)

messages.append({"role": "tool", "content": result, "tool_call_id": id})This approach avoids one of the biggest MCP failure modes: non-deterministic tool selection and malformed JSON outputs. The SLM is constrained, predictable, and observable.

MCP Registry: Decoupling Tools from the Brain

The MCP Registry is deceptively simple, but it is one of the most important components in the system.

It exposes endpoints to register tools and to query them by name. Each entry contains metadata and a pointer to the actual executable binary. That’s it.

What this buys you is architectural freedom. The orchestrator never hardcodes tool locations. New tools can be published, old ones can be deprecated, and versions can be rolled forward or back without touching the SLM service.

// From MCPServerController.java

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/api/v1/servers")

public class MCPServerController {

@PostMapping

public ResponseEntity<MCPServer> register(@RequestBody MCPServer server) {

// Registers a new tool with its metadata and binary location

return ResponseEntity.ok(service.registerServer(server));

}

@GetMapping("/{name}")

public ResponseEntity<MCPServer> get(@PathVariable String name) {

// SLM fetches tool details (inputSchema, binaryUrl) at runtime

return service.getServerByName(name).map(ResponseEntity::ok)...

}

}In practice, this means you can treat MCP tools the same way you treat microservices: independently deployable and discoverable at runtime.

Why WASM Is the Execution Boundary

Executing MCP tools as native processes is risky. This is why we execute all tools inside a WebAssembly (WASM) runtime. Each tool is compiled into a .wasmbinary and executed inside a Wasmtimesandbox.

In our Artifactory, tools are served as static versioned binaries:

# From artifactory/main.py

@app.get("/binaries/{filename}")

async def get_wasm(filename: str):

file_path = os.path.join(STORAGE_DIR, filename)

if not os.path.exists(file_path):

raise HTTPException(status_code=404)

# Serve the binary with the correct media type

return FileResponse(path=file_path, media_type="application/wasm")

The Orchestrator then executes these tools via a secure stdio bridge:

# How the runtime is invoked in slm_server.py

server_params = StdioServerParameters(

command=RUNTIME_SCRIPT, # path to our secure wasm runner

args=["--url", binary_url], # binary URL from the Registry

env={**os.environ}

)

# Establish a sandboxed connection

read, write = await exit_stack.enter_async_context(stdio_client(server_params))

session = await exit_stack.enter_async_context(ClientSession(read, write))Dynamic Tool Loading in Practice

The WASM runtime does not ship with tools pre-installed. Instead, tools are fetched on demand.

When the orchestrator requests a tool execution, the runtime checks its local cache. If the binary is missing, it pulls the correct version from the Artifactory, loads it, and executes it in isolation.

This makes deployment trivial. A tool is just a binary. There is no npm install, no virtual environment drift, and no “works on my machine” problem.

Handling Real-World Constraints: The Fallback Strategy

Not everything is immediately WASM-friendly. Some tools require complex host integrations or IO patterns that are difficult to bind early on.

Instead of blocking progress, the MCP Workbench supports a simulation fallback. The Registry still advertises the tool as available, but the runtime transparently executes a host-backed implementation until a full WASM version is ready.

This keeps the orchestration logic stable while allowing gradual migration toward full sandboxed execution.

WIT: The Contract That Keeps MCP Honest

One subtle but critical piece of the system is the use of WebAssembly Interface Types (WIT).

WIT files define the exact shape of tool inputs and outputs. This is not documentation—it is an enforceable contract. When the SLM passes JSON to a tool, the runtime validates that it matches the expected schema before execution.

This eliminates an entire class of errors where a model produces syntactically valid but semantically incorrect payloads. It also enables true language independence: tools can be written in Rust, Go, or TypeScript, and the orchestrator treats them uniformly.

Why Not Just Use Node.js for MCP Tools?

This question comes up often, and the answer is pragmatic.

Node.js tools run as native processes with broad access by default. They bring runtime dependencies, environment configuration, and security concerns that grow with scale. WASM tools, by contrast, are atomic binaries with a strict sandbox and a stable execution model.

For a dynamic MCP system where tools are discovered and executed at runtime, WASM is simply the safer and more scalable choice.

Demo & Source Code

📦 GitHub Repository: https://github.com/tpushkarsingh/mcp-client-workbench

🌐 Read more tutorials: https://blog.slayitcoder.in

💼 Connect with me on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/tpushkarsingh

Closing Thoughts

The MCP Workbench shows that MCP does not have to remain a toy protocol used only in demos. With the right architecture, MCP can support dynamic discovery, secure execution, and deterministic orchestration.

By separating discovery, storage, execution, and reasoning, the system allows AI capabilities to evolve independently—exactly how modern infrastructure is supposed to behave.

If MCP defines how models talk to tools, this workbench defines how that conversation survives the real world.